November 2022: In early 2022, I first learned about the Cave of the Tayos when my brother, Jesse tagged me on a Facebook post from Outdoor Magazine with a message, “Let’s do this.”. According to the article, it is a cave not only full of tarantulas, scorpions, and screaming oil birds, but also believed to contain a hidden ancient golden library of tablets engraved with alien like symbols that may hold the secrets to the origin of civilization. Even first man on the moon, Neil Armstrong was lured to the cave on an expedition in 1976 in pursuit of its legends.

The idea of reaching the cave, I was worried, would be too expensive and dangerous, but I was determined to try, so I responded to Jesse and said, “yes, let’s do it.” My motivation to visit the cave was only strengthened when other strangers in the Facebook forum chimed in on our chat to tell us it was impossible to visit the cave and that we would die. My only response to these naysayers was, ” I will tell you how it was when we return”. I made sure to follow through with my promise too.

About Tayos Cave

In the 60’s and 70’s the southeast of Ecuador was uncharted rainforest. Even today, the area remains wild. But during that era, it was a place where few outsiders ventured. The land belongs to Shuar Indians, a tribe with a warrior like reputation that historically managed to fight off Incan and Spanish invasions. The Shuar had a savage reputation of head hunting, cannibalism and for keeping the shrunken heads of their enemies as war trophies. Deep in the Shuar jungles where the Amazon rainforest meets the Incan foothills, exists the Cave of Tayos, an extensive underground network of tunnels still vastly unexplored. Until recently the cave of Tayos was only known to the local Shuar Indians who have been descending into the cave for generations with vine ladders to hunt the Tayos or oil birds. The cave has always been sacred to the Shuar and according to their beliefs it is home to the spirits of giants.

Explorers were first led to the region when a priest, Father Crespi, who had lived with and developed good relationships with the Shuar displayed his collection of treasures gifted to him by the Shuar, some said to be from Tayos Cave. Father Crespi had a small collection of artifacts, some made of gold with mysterious symbols of pyramids and Mesopotamian like writings and shapes that resembled antiques and writings of a similar nature of ancient artifacts found in the middle east or North Africa. Crespi’s collection unfortunately would end up being stolen before it could ever be properly studied by archeologists.

Then in the 1960’s, a Hungarian/Argentine explorer, Juan Moritz, a wealthy businessman inspired by the artifacts of Father Crespi, went deep into the jungles of the Shuar seeking the source of the artifacts. It was on this expedition that Moritz discovered Tayos Cave, where he journeyed into its depths to discover what he believed were tunnels carved by methods unknown to man, crystal sarcophagus’s containing the skeletons of giants and a library of enormous golden books inscribed with alien like symbols. The books were too heavy to remove and back then the expedition lacked any cameras to record their presence. After the expedition, Moritz pleaded with the Ecuadorian government to let him lead a return expedition to the cave to find and retrieve the library.

Moritz did return to the cave with the Ecuadorian military, but the expedition ran out of funding before it could explore the cave and locate the library of golden books. Moritz reached out to others to organize a return expedition, but none would agree to his strict terms and subsequently Mortiz refused to cooperate and share his knowledge with any future expeditions. Moritz never did return to the cave.

For a decade or so afterwards, the cave remained mostly forgotten until Stan Hall, a Scottish treasure hunter traveled to Ecuador to look at Father Crespi’s collection and he too became interested in the cave. Then in 1976 Hall put together one of the largest cave expeditions in history that included the Ecuadorian military and American astronaut, first man to step on the moon, Neil Armstrong. Neil Armstrong some say, saw something unexplainable on the moon that he publicly was reluctant to discuss, and this is why he became interested in Tayos Cave and its potential association with aliens.

The Hall expedition did explore the cave and find some ancient archaeological artifacts, but no ancient golden metal library or crystal sarcophagus was discovered. The Shuar in the area claimed that the explorers had entered the cave from the wrong entrance and that the true location of the library remained a guarded secret.

Despite the failure of the expedition to find the metal library, important artifacts in a burial ground inside the cave were found showing that a more sophisticated culture had once lived in the area. Neil Armstrong himself said that his adventure in the cave rivaled that of his time on the moon.

Hall did not want to give up on his mission to find the metal library and even convinced Neil Armstrong to join a second expedition, but the expedition never occurred because of political instability in Ecuador.

Then the location of the library seemed doomed to disappear forever when all of the people with any knowledge of it including Moritz died. A second man, who claimed to have inscribed his name on one of the metal books, claimed the true cave entrance was located in a different area near the original entrance. Stan Hall and this man were coordinating to identify the location of the entrance when the man was murdered before any real information about the alternative entrance could be revealed. Now it seems if the metal library ever existed, it may have disappeared with the deaths of these two men.

There have been subsequent expeditions into the cave, and all have fallen short of finding the library. Geologists have determined the tunnels were forged by natural processes instead of by alien machines and attention has turned away from the cave’s alien legends to its ecological importance. The cave continues to be sacred to the Shuar Indians but in effort to gain some money off of its notoriety, the Shuar have started to allow tourist expeditions into the cave. However, Tayos cave has by no means become a mainstream tourist attraction and few visitors enter the cave on an annual basis. Many Shuars are not thrilled by allowing tourists into the cave and believe that the presence of outsiders have angered the cave’s spirits. For now, the cave is open to tourist but only with permission from the Shuar and its continued availability, as well as the discovery of any treasures, is unclear.

The Cave of Tayos is located near the border of Peru where the Amazon rainforest meets the foothills of the Andes.

Getting There

My search for information about the cave came up with very little information from anyone that had been there apart from scientific expeditions or articles about aliens. Although I had read that it was now possible for tourists to visit the cave, there was very little information to support this. I decided to reach out to a guide, Robert Vaca/owner of Amazon Tours, who organized a previous trip of mine in Ecuador to visit the Huaorani Tribe in Yasuni National Park. He was well connected with the Indigenous cultures of Ecuador, and I hoped he might have some connections to make Tayos work. After a month, Robert responded to inform me the trip was possible. He had found some contacts that coordinate with the Shuar that can lead us into the cave. Over the next 6 months I worked with Robert to finalize the details including costs of the expedition. Our plan would involve travel overland by car from Quito to Macas, a gold mining town near the Peru border, where we would meet our expedition team led by an Ecuadorian climbing expert, a Sergeant in the Ecuadorian Special Forces, a soldier friend of the sergeant trained in jungle medicine, a cook and a Shuar Indian guide.

From Macas we would drive deeper into the jungle along a newly paved road built to strategically defend the border region from Peru, a country that Ecuador fought a short war with in the early 80’s over the oil and mineral rich border region.

We would then catch a Shuar boat to a remote village that can only be reached by boat and climb 4-5 hours through the rainforest uphill along muddy difficult tract to get to the entrance of the cave. The cave is only known to have two entrances, and both involve entering into a deep pit via a long rope descent. Our plan was to spend 2 nights camping and exploring inside the cave before returning via the same route we arrived.

To begin the trip, I flew to Quito, capitol of Ecuador, located high in the Andean mountains at 9,000.’ where I met two of my travel companions, Wes and Jimmie. From Quito we traveled by vehicle to Macas.

Quito Old Town/view of largest neo-Gothic church in the world built in the 1800’s-Basilica of the National Vow

My guesthouse, an old spanish home dating back to the 1700’s that also sits on top of Spanish inquisition tunnels where prisoners were tortured and executed. Now the location where guests eat breakfast in mornings.

The Amazon Rainforest Meets the Andes

After a long 8-hour drive that took us over a mountain pass of 11,500′ passed the 20,000 ‘ active snowcapped volcano, Cotopaxi, and through a series of mountain tunnels, we finally arrived at the town of Macas, where we met my brother and his girlfriend in a house they rented from a local family in the outskirts of town. We met our guide, Sergeant Yaco and the rest of our caving crew at night and sorted through our expedition gear (tents, sleeping bags, cave lights, food, mud boots, etc.), discussed trip details and then had a birthday dinner, cake along with a few celebratory beers for my brother’s 40th birthday.

The next morning, we all piled into a van for a two-hour drive into the jungle of Puerto Yukianza, a hilly rain forested area. We knew we were in the Amazon rainforest, when we stopped to use a toilet at a small shop off the road, and a live vampire bat nearly dropped on to my brother’s head.

It also rained hard that morning. Rain poured the entire drive leaving me worried that we would have to hike in the rain and in the mud. Luckily, as soon as we reached Puerto Yukianza the rain stopped. We boarded a small open top boat operated by the Shuar government to transport Shuar to their villages, only accessible by boat.

View of Namangosa River. where we caught our boat

Lexie Overlooking the Namangosa River

We were given life jackets and I soon realized why when we departed on to the river. Raging rapids fed by the areas incessant rains lashed our boat and it seemed obvious to me that one wrong turn by the operator in the rapids could easily capsize our tiny boat. We traveled for 30 minutes down the river of Namangosa, Zamora River and Santiago River dropping off various Shuar Indians on remote riverbanks in the jungle with no appearance of a village anywhere nearby. We passed deep rainforests and roaring waterfalls pouring from jungle clad cliffs into the river.

The Shuar public ferry boat

Us traveling down river in the boat

Then it was our turn to be dropped off on a riverbank. We met our Shuar Indian guide, Alfonzo at the riverbank and from there we hiked straight up a steep muddy jungle trail to a Shuar village. The conditions were hot and humid, and I instantly became drenched in sweat.

Jungle clad hills we hiked through

About the Shuar Indians

After a difficult hour-long steep hike passed a Shuar graveyard. The bodies are not placed inside gaskets but are instead buried directly into the ground and bodies are placed on family plots with no markings to identify the individual. The rainforest we passed was well preserved with few clearings and evidence of agriculture. The Shuar village was a small cluster of huts with a few children playing in a field. The Shuar although now wearing modern clothing and modern hairstyles still practice a traditional lifestyle of subsistence farming and live a rural life in relative balance with nature. Due to the arrival of Christianity, they have abandoned head hunting, cannibalism and their famous custom of shrinking heads but they still are perceived as warriors and are well regarded in the military especially for their jungle combat abilities. The Shuar although Christain still maintain their traditional beliefs and have hybridized Christianity with animistic beliefs such as a belief in traditional sprits. The Shuar are the traditional guardians of the cave and reportedly not all are happy that some Shuars are now leading foreigners into the cave for revenue. We didn’t see any signs of resentment, but we also didn’t see many Shuars since only a few dozen people live in the village and most stay out of sight. But I did read reports of cavers exiting the cave only to be greeted by angry Shuar women who proceeded to whip them with vines even though the cavers had Shuar guides and permission to enter.

After spending an hour in the village and eating lunch, we set off on the long 3–4-hour hike deeper into the rainforest and further uphill enroute to the cave entrance.

Shuar village with a recent installation of electrical powerlines

Our Shuar guide, Alfonzo showing us cannibal tools he found inside the cave

A rickety Suspension bridge missing some of its wooden boards hanging 100′ above the river below that swung as we crossed

Descent into Tayos Cave

We reached the cave in the early afternoon, and I was exhausted. But my attention quickly turned to our next task, descending almost 200 feet by rope into the dark jungle pit that lay before us. This was also a pit with what sounded like shrieking hell demons below. But instead of demons, this was the sound of the Tayos birds that lived inside the cave.

We set ourselves up with a harness and helmet and prepared our packs for the descent. Lexie volunteering to go first, my brother next, then one by one we descended by rope and disappeared into the cave.

Even know I had done this kind of thing before in Mexico and other places, the first step off the cliff, with only the rope to keep you from plummeting to certain death being impaled on the rocks below, is always a leap of faith.

I leaned back but my pack tied to the rope below me became en-tangled and I spun off balance and flipped awkwardly to the side. The guide yelled at me to move the rope to the center between my legs and once I made this correction, my balance was normalized. From then on, I was able to sit back and enjoy the one-minute descent to the bottom of the cave as the birds shrieked around me. Soon I was in a different world surrounded by huge limestone walls looking up at the small glint of sunlight above that now seemed very distant.

My brother before his descent

Jesse descending into the cave

Jesse descending to Tayos Cave

View of the descent from the bottom of the cave

View of the descent from the bottom of the cave

Creatures of the Underworld

Once at the bottom of the cave, we were in a completely different world and now we were at the mercy of the creatures that lived here, and it became instantly clear that there were many. Like most cave ecosystems, there is a bird or bat that lives in the ceiling and its droppings that fall to the ground provide food to the bottom feeders. In this case the bottom feeders are cock roaches, beetles and cave crickets. The bottom feeders are then prey to the predators of the cave, such as tarantulas, other various spiders, centipedes, and scorpions…….. We didn’t see any snakes but with so many birds as prey, we knew there were definitely snakes in the cave.

The ground was thick in guano especially for the first hour or so into the cave. This is because there were more Tayos birds roosting in the walls. The more guano, the more bugs. Cockroaches, spiders and scorpions were a common sight in the cave, and you didn’t have to look far to find one. Tarantulas and whip scorpions were huge and menacing but their bite besides a sting would not kill. Other spiders in the cave and the small scorpions on the other hand were venemous and our goal was to avoid being bitten by them. It would not be easy to be medically evacuated out of the cave, especially at night.

To protect ourselves from these nasty critters, we wore mud boots, pants, and gloves. The rule of thumb was to never place your hand or butt on a rock until you shine your flashlight on it and make sure it isn’t already occupied. There were a few occasions where this rule came in handy. Once on the toilet and again when I laid my hand down on a rock to use it as a tripod. In both cases a scorpion came close to biting me or someone else.

Tayos or oil bird that live on ledge along the walls of the cave

Giant whip scorpions which are pretty much huge spiders

Posion dart frog found at the bottom of the descent. We were very careful not to touch this little guy, whose venom from his skin can potentially pass through human skin or from skin via amucous membrane causing instant death

Transparent giant cave cockroach. These cockroaches have little pigment since they live in darkness and their internal organs are visible

Giant Goliath Tarantula size of my hand with blue limbs. These guys were massive but hard to pohotgraph since they usually escaped to their burrows when detecting us

Scorpion-this is maybe the most venemous creature in the cave and the most dangerous

Cave Spider

Introduction to Tayos Cave

We had about an hour to hike through the cave before reaching our campsite, which involved a 20′ rope descent. It was clear to us right away why some of the explorers thought the cave was forged by giant machines. The flat top ceilings with perfect right angles to the walls did appear unique as if sculpted by humans but geologists have studied the cave and determined natural forces are responsible for this.

We had to very deliberately choose each step when walking in the cave as we climbed over boulders and loose rocks. A wrong step could easily sprain an ankle or worse. The cave was humid, dusty and muddy and it didn’t take long before we were covered in filth and sweat. Each hand hold was closely inspected for the presence of insects but on the most part the insects would scurry away from light and into their dark holes.

Wes Looking into the Depths of the Cave

Rapelling a 20′ wall on the way to our campsite

Our Campsite in the Cave

Our campsite was a flat area of dusty rock in the middle of a huge dark cavern with a high ceiling. There was no natural light and without our flashlights, it was completely dark. The Tayos birds were in the ledges all around us and would constantly squawk in disapproval of us. To protect us from the bugs on the ground, we laid a plastic tarp on the ground to put our tents on top of it, giving us some separation from the insect world. Since we didn’t have chairs, we would sit on rocks when relaxing at the campsite. We commonly would share a rock with a scorpion or spider but most of the time, they would stick to their side of the rock, us ours and there would be peace.

About 20 minutes from our campsite, further into the cave was our washing area, a small trickle of water that seeped through the ceiling high above creating a mini waterfall just large enough to shower every night and to collect clean drinking water for our camp. Although the water was clean from being filtered through the thick limestone above, we still filtered it to be safe. The bathing area was not easy to get to or to return from and by the time I hiked back to camp after bathing I was already covered in sweat. On one occasion, I walked back by myself thinking our camp was nearby and I ended up taking a wrong turn almost getting lost in some huge treacherous boulder field that led to a dead end. When I finally returned to camp, I discovered Jimmie and Wes had also become lost in the same area.

Our campsite

Jesse and Lexi at our campsite

In order to protect the fragile cave ecosystem, the Shuar set up a portable wooden toilet a few hundred yards from our campsite where there were mounds of guano. This area was selected because there are a lot of scavenging insects, and any organic materials rapidly decompose including human waste. Once the trip was over, the toilet would be relocated to another area a few feet away and a nearby shovel was used to bury the human waste to allow it to decompose under the cover of guano. To say that the area was unpleasant is an understatement. Between giant venemous purple centipedes, a scorpion on the toilet and the ground pulsating with heaps of feeding cockroaches, this was not a place to linger. Business was done with no time to spare.

The area where our bathroom was in a guano pile that the oil seeds discarded from Tayos birds are germinating into small stalks that only grow a few feet tall.

Our toilet, a small block places over the guano piles to help keep the cave clean. A scorpion on the toilet is a reminder to always shine your flash light before sitting or touching

View of where the toilet area is located from our tent. It is probably the most adventerous toilet experience on Earth.

Next to our tents, was the dining area, where our cook would prepare our meals. This area was pretty welcoming with candlelight and music from a radio. Our cook would prepare meals of pasta, potatoes, and starchy energy packed meals that we quickly consumed at the end of each day along with some strong rum.

Our campsite and dining area

We were shocked to spot a possum near our dining area, which I didn’t expect to see so deep into the cave. We decided he was likely after the Tayos bird eggs.

Possum by our campsite

Night in the Cave

Sleeping in a cave is not for everyone. First of all, we slept on the hard ground without a sleeping pad. We rented tents and sleeping bags for the trip, but we didn’t have sleeping pads. I used my sweaty backpack as a pillow, and I slept on top of my sleeping bag because the temperature in the cave at night stayed pretty warm except in the early hours of the morning when it would dip low enough to where I needed to get into my sleeping bag. There was the constant darkness with no sunrise, sunset or even stars since we were deep in the cave. The constant shrieking throughout the night of the Tayos birds that nested all around our campsite, best described by one traveler as sounding like demons murdering babies, was impossible to get used to. Some birds would leave the cave at night to harvest oil nuts that they would bring back to the cave and consume.

As I lay awake for most of the night, I would study the sounds of the birds. I realized the sounds were not all the same and there were different calls. There was the annoyance call directed at us and our flashlights and there was a sound they used for echolocation when they flapped their wings very hard. Tayos birds are the only fruit eating nocturnal bird and meant to be the only bird that use echolocation. Then there was a sound they made in the middle of the night that sounded like a giant Pterodactyl was swooping through the cave. Needless to say, I didn’t sleep well while I was in the cave.

Sounds of night in the cave from our tents

Venturing Deeper into the Cave

The next morning, we had breakfast and set off with our crew to explore the cave. There are 5 kilometers of know caverns, but it is believed by many that this is just the beginning of a massive cave system that extends well beyond this. Our guide established one main rule, ” don’t go off alone anywhere and stay together.” This is especially important in a cave as big as this one. if someone were to fall, hit their head and get knocked unconscious, or get lost, this would be the place where you could easily disappear.

We started the day by hiking to the 2nd entrance of the cave, another pit with a 200′-foot drop from the jungle above. Hundreds of tayos birds roosted along the walls of the pit. Our guide explained that no one enters the cave from this entrance because it would disturb too many Tayos birds. This was also the area that the Stan Hall expedition found ancient artifacts in what they determined was a burial area located beneath where a beam of sunlight strikes the ground.

My brother standing in the 2nd cave Entrance. Angry Taos birds shriek in the background

My brother Jesse and I on another one of our many adventures

Many of the cave rocks appeared to be carved in blocks some geometrical symmetrical

Jimmie looking into a cave shaft

On the most part we didn’t have to enter any small spaces but on occasion we did have to crawl on the ground and squeeze in between boulders. Luckily, these areas didn’t have any Tayos birds so there were fewer insects.

Jesse ducking down below a ledge

Stalagtite formations

Lexie posing by some flat smooth rocks

Wes posing on a boulder with his shadow cast behind him like a giant

There are almost 5km of known cave tunnels, but it is believed that there are many more branches of tunnels leading to other cave networks that are connected to Tayos cave. On occasion we would come across small offshoot tunnels and wonder where they led.

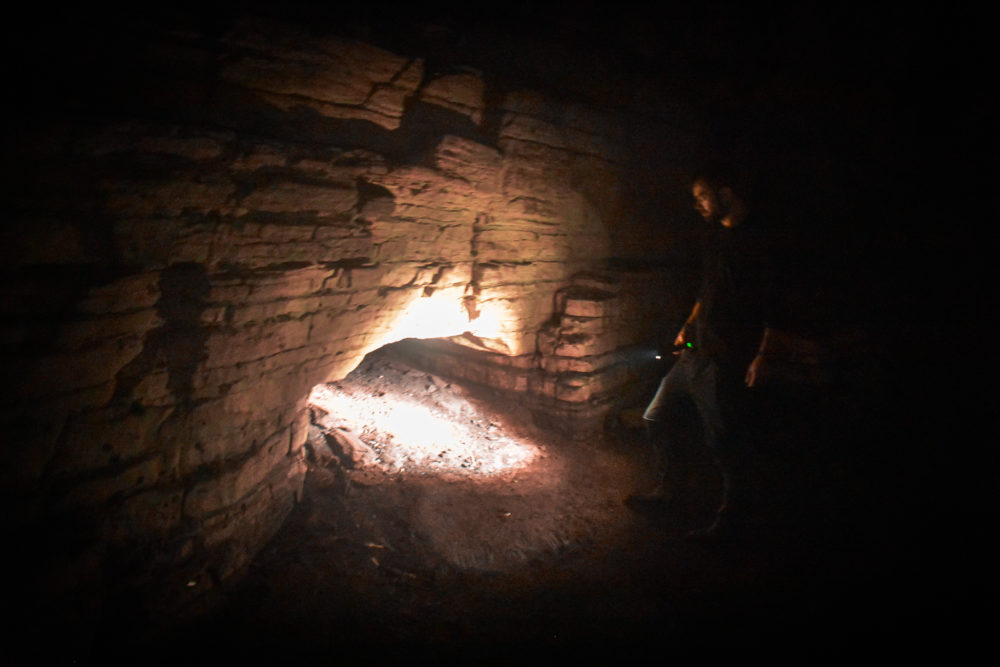

Jesse inspecting a small offshoot tunnel

Exploring the cave was a highlight and knowing that there are probably less than 500 people that have entered the cave including us is a real privilege.

Jesse inspecting some interesting shaped rocks

Some sections of the cave were tough going and involved rope and some pretty delicate footwork to avoid falling off a ledge.

Negotiating a steep section of rock with ropes

After a long stretch of narrow tunnels and walking along slippery rocks and negotiating ropes, we came to the trophy spot, a waterfall with a small pool of water where we all took turns having a swim in its cool refreshing waters. We even spotted some cave lobsters and parasitic worms that hung from some of the cave arches waiting for any insects to cross their path, become ensnared and consumed by their digestive juices.

Jesse in the waterfall

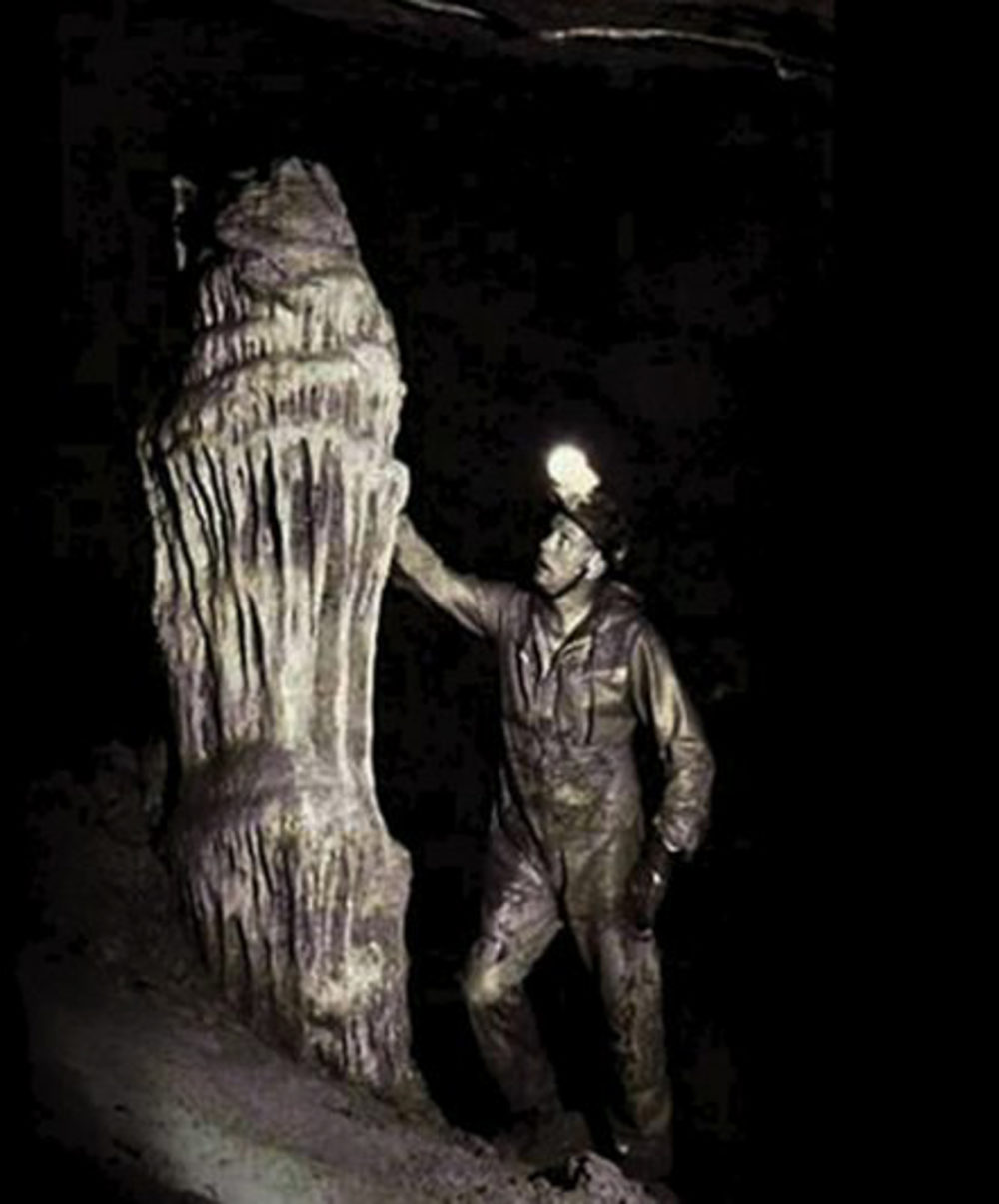

I kept thinking how amazing it was that I was walking in the same footsteps of one of the greatest explorers to have ever lived, Neil Armstrong. Then when we came to a stalagmite where Neil Armstrong took a photo of himself in the cave, we all took turns posing in the same spot as he did.

Neil Armstrong posed for a photo in 1976

Me posing next to where Neil Armstrong posed for a photo in 1976 (see left photo)

We stopped to have lunch in one giant amphitheater. This was a magical room with giant tiered limestones stones that led back hundreds of feet to the rear of the room. While in the amphitheater, in one of the deepest sections of the cave, we decided to turn off our flashlights and immerse ourselves in total darkness and silence for a few minutes. The silence was so loud, you could hear it and the darkness was interrupted by a small glowing ball of blue light that levitated in the air and moved from one section of the room to the other. It was so faint that I thought I was hallucinating but others confirmed they saw it too. We never did figure out what it was. It was likely some kind of bioluminescent bug, but this was a part of the cave that didn’t have any visible bugs.

Another strange event occurred when my brother was exploring a random dead end of one of the caverns, we passed on the way back to our camp. In a small tarantula hole on the side of a wall, my brother found a peculiar looking stone that was round, polished and quartz like. But what was really remarkable about this stone was that it glowed bright, blue in the dark and it looked nothing like any other stone we had seen in the cave. Even our guides were perplexed by it.

Jimmie in the amphitheatre

Exploring the amphithetre

Is the Legend of the Cave True

We didn’t find or expect to find any signs of a gold, metal library of alien books. But if such a treasure exists it is possible that it could remain hidden somewhere deep inside the elaborate network of tunnels in Tayos Cave. I asked our Shuar guide if he believed the library existed and he said he did not but that his father was part of the Armstrong expedition in the 70’s and he watched the Ecuadorian military haul off loads of mysterious artifacts from the cave. If the metal library had been discovered and removed, there has been no sign of it, and it has not resurfaced in any private antique collections or auctions anywhere. So, in all likelihood it never existed and was just a tall tale created by Mauritz. But why? Mauritz was a wealthy businessman who didn’t need more money. he seemed genuinely dedicated to finding the library to prove his hypothesis that Europeans and Asians are descended from the Americas or that there are tunnels underground connecting the continents. Why would he risk his reputation to return to the cave and be exposed as a fraud if the library didn’t exist. Also, there were others that claimed to have seen the library and all stories of the treasure aligned with one another. In all likelihood, this is just another one of those mysterious that will never go answered.

But there are other mysteries of the cave besides the metal library of alien books. There are also the mysterious glowing lights seen by some visitors. We also saw a floating blue light in the darkness deep in the cave. But this could be an insect with bioluminescence. There are still many insects in the cave that are not known to scientists. The Shuar do believe that there are spirits of giant cave dwellers that live inside the cave and on one expedition oversized prints of human like footprints were found in a corridor of the cave that few visitors are able to access. Strange thundering sounds inside the cave have also been heard by some. To many Shuars, this is just evidence of what they already believe are giants living inside the cave.

Exiting the Cave

On our last morning after spending two nights in the cave, we packed up all of our gear after eating breakfast and hiked to the same entrance, where we would be exiting the cave. Our same rope was still there. Our Shuar guide had arranged for Shuar village men to be at the cave entrance at this time to help pull us out by the rope so that none of us, except for the guides would have to exit via the more exhausting manual abseil technique. The Shuar guide was the first to go up the rope and made the manual technique look easy. He was up to the top in 10 minutes. Once on top, the guides set up the rope pulley system to raise us all up from the cave. We were fortunate that it wasn’t raining. I read reports from previous expeditions of tropical downpours sending torrents of water streaming into the cave making it impossible to ascend. Lucky for us, the weather was cooperating. One by one we were all raised to the top by a group of 5 Shuar boys who heaved us out of the cave in approximately 10 minutes each. I was the first to go up since I was the heaviest and the guide determined that it was better to raise me while the pullers up top were still feeling strong. I bounced up and down as the Shuar pulled me and the bungy feeling was a little unnerving, but nothing compared to the Cave of the Swallows, a cave I visited a few years back. Once all of us were on top, we walked all the way back to the Shuar village and the riverbank and were picked up by the Shuar water taxi which took us back to where our van was waiting on the road. From there we had one last dinner together parting ways at different cities on the way back to Quito, where some of us spent our last day in Ecuador before returning home. It was a long day and impossible to believe that I had started the day in the cave and ended it in a hotel in Quito.

Recommendations for the Cave

These are a few tips I recommend to improve your trip:

- Make sure you are well hydrated and acclimatized before starting the hike to Tayos cave. The dehydration can be a killer and you need to be ready for the long grueling up-hill humid hike.

- Bring hiking or a walking stick to support you on the hike.

- Bring a day pack and pack light. You only need one clean pair of clothing for sleeping at night.

- Porters are available for hire in the Shuar village, or you can ask to have a horse carry your gear.

- Mud boots-at first, I thought the mud boots were a hindrance because the mud on the trail had mostly dried up. This would have been a different experience in the rain. But the boots were beneficial inside the cave where the guano and mud were pretty thick in parts. The boots provided good foot protection from the mud and creatures that live in it. Just be sure to get mud boots with good traction.

- Bring a pair of climbing gloves to help you hold on to the rope and maneuver inside the cave. You will often find yourself grabbing on to rocks and most of the time these rocks will have venemous insects on them.

- Bring ear plugs to block out the incessant screeching of Tayos birds so that you can sleep at night.

- Bring a sleeping pad because the rock surface of the cave is hard and not pleasant to sleep on.

- Bring a good caving light and back up batteries. If you have a source of power to re-charge the batteries, bring this. Bring a second small flashlight just for reading in your tent or walking around camp.

- Bring flop flops or a comfortable pair of shoes for walking around camp. Keep in mind there are still scorpions around camp, so you still need to be careful where you step.

- Bring lots of insect repellent because the sand flies are horrendous and most of us were bit up very bad.