May 2023: I initially fell in love with the Buddhist regions of the Himalayas in 1998 when I visited the Indian Ladakh and Zanskar and spend a few months traveling and trekking in the region. Ever since then I have returned to trek in Bhutan/2005 and in Tibet/2010, where I traveled to Everest Base Camp to reign in New Years Eve. Few places in the world can rival the combined exotism of visiting Tibetan Buddhist culture among the soaring peaks of the Himalayas and this includes the Buddhist Mountain Kingdom of Mustang in northern Nepal. With a baby coming in September, I wanted to get a good adventure in beforehand and Mustang was the perfect place for one. This is the story of my two-week trekking trip to Mustang joined by my friend Jimmie, and brother, Jesse to explore its desolate mountain valleys and its unique Buddhist culture.

Location of Mustang in northern Nepal bordering China Tibet

The Upper Mustang was a closed Buddhist kingdom until 1992 off-limits to foreigners. Since then, even though the kingdom has slowly opened up to the outside world, it continues to remain isolated because of its extreme mountain environment and deliberate controls established to preserve its culture, such as a requirement for foreigners to obtain an expensive permit, and guide to enter the region. All of these factors have helped to remain culturally unique. Despite the controls to regulate tourism, the tourism industry is one of the most important aspects of its economy along with animal husbandry, farming and trade.

Mustang was an independent kingdom flourishing from trade between India and China from the 15th to 17th century. Then in the 18th Century it was annexed by Nepal but remained semi-autonomous with its own monarchy until 2008 when Nepal became a republic and abolished both its own monarchy as well as Mustang’s.

Other travelers I know that have been to Mustang have all raved about its beauty and how it is seldomly visited by other tourists giving it a rustic charm. Outside of the Tiji festival, tourists are still known to be rare, and this was our experience. On our trek we rarely encountered foreigners and in most tea houses, we were the only guests.

Despite being historically isolated, Mustang is changing as inroads of modern life are making their way into the region. A gravel road connecting greater Nepal to the Chinese border was built 7 years ago and this has led to increased tourism and developmental works such as electricity that have brought expedited change.

Even though I wish I had visited Mustang before the construction of the road, there was still enough natural and cultural beauty to attract me and with the rapid rate of change as the modern world encroaches, I felt that if I was going to visit Mustang, it was now or never.

Despite welcoming new roads and outside influence, Mustang has avoided opening its flood gates to foreigners like other regions of Nepal that have become inundated with tourism especially budget-oriented backpacker travelers. Mustang has instead chosen to slow the adverse effects of mass tourism through regulations and requiring that all foreigners pay for a 500USD Permit to enter, which is valid for a minimum period of 10 days. Additionally, there is a set limit to how many permits can be issued, an approved guide is required and a minimum of two tourists required for each permit. Since trekking in Mustang also overlaps the Annapurna Conservation region, we also had to pay a much smaller fee of 25$ for entering into this area. To obtain the Mustang Permit and arrange the trek, I reached out to Dawa Pun, owner and guide for the trekking company Tramping in Nepal and I wired him 500USD for our permits, which were obtained before our arrival. Police checkpoints in Mustang do check for these permits and have turned away tourists trying to enter without them.

To reach Mustang, Jesse, Jimmie and began by flying to Katmandu on Qatar Airways from Doha, Qatar. We spent one night in Kathmandu and then took what was supposed to be a 6-hour bus ride to Pokhara but because of road construction and traffic was actually a 10-hour bus ride. It also didn’t help that 30 minutes after starting our long bus journey the first bus died on the side of the road, and we had to wait for a replacement bus to come and pick us up. From Pokhara we needed to get to the gateway of Mustang, the small mountain village of Jomsom, which can be reached via a short but scary 20-minute flight or a long 8-to-10-hour drive on horrendous mountain roads.

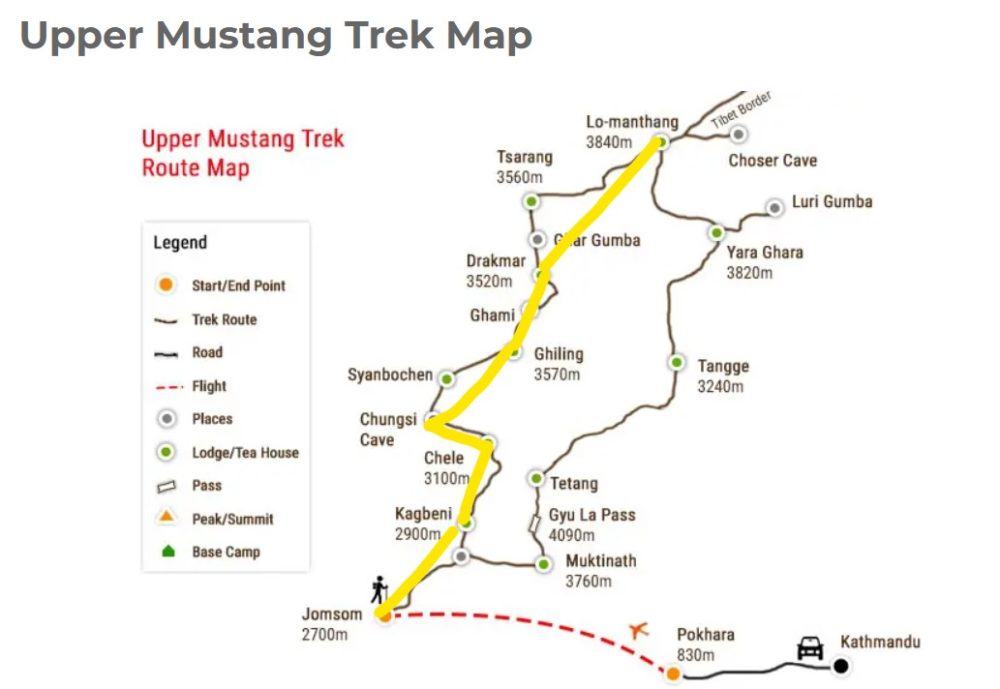

From Jomsom, our 77-mile trekking itinerary with family run village tea house stays in Mustang was as follows:

- Day 1: 20-minute flight to Jomsom via Tara Air, 4-hour trek along to Kagbeni

- Day 2: 6-hour trek to Chele

- Day 3: 10-hour trek to Ghiling

- Day 4: 7-hour trek to Drakmar

- Day 5: 7-hour trek to Lomanthang

- Day 6: Horseback riding and jeep to visit various sky caves around Lomanthang

- Day 7: Jeep drive to Jomsom

- Day 8: 8-hour Jeep drive to Pokhara

Route of our trek

Getting to the gateway of Mustang, Jomsom is not easy and there are only two routes: road or air.

- Road: The road is long and treacherous via the mountains and can take 10 hours or more via private jeep and even longer in a bus. The road is under construction and faces constant maintenance because of poor weather, mud and rockslides. Accidents and fatalities are commonplace. The road is subject to constant closure especially during monsoon season, which begins early June around the time we embarked on our trip to Mustang.

- Air: Compared to the 10 plus hour drive, the flight is only 20 minutes long via one of Four domestic airlines; Buddha, Summit, Yeti or Tara Air. All fly small old and rickety 20 capacity twin turbo prop planes designed for high mountain and short field landings. The flight is short and convenient but adrenaline inducing. Flights only occurr early before cloudy and windy conditions set in rendering the flight too dangerous. Weather along this route is notoriously bad and flights are often cancelled. The route is plagued with a history of fatal plane crashes. The most recent crash was exactly one year ago when a Tara Air flight crashed into the mountain near Jomsom airport in poor visibility killing all on board. Nepal in general has one of the poorest aviation safety records of any country in the world and only a few months prior to our visit A Buddha Air flight crashed just outside of Pokhara killing 100 passengers.

On the morning of our flight, we were blessed with clear skies and our flight on Summit Air went as scheduled. Besides the three of us, our flight was full of Hindu pilgrims from India that were visiting the Hindu temple of Muktinath sacred both to Buddhists and Hindus. Seats were first come first serve and we had to battle pushy determined elderly Indian pilgrims half our size for window seats facing the Annapurna Mountain range on the right side of the plane. The plane was stuffy with poor ventilation and the seats uncomfortable, but we figured it was only for 20 minutes. As soon as we took off, it seemed as if we were scraping the edges of the mountains and feeling the sudden jolts of mountain turbulence. Our route took us through the deepest mountain gorge in the world parallel to the 27,000 Annapurna Mountains, which towered above us. As we flew the Hindu pilgrims on our flight chanted prayers pleading with the Hindu God Shiva to bless us with a safe flight. It was surreal looking out the window among the world’s tallest mountains while other passengers prayed out loud to Shiva as we were bounced around in the little plane. But the best part of the flight was saved for last. As we turned into the narrow mountain valley where the airport to Jomsom was located, the pilot hugged the ridge of a mountain and then conducted a steep G force inducing spiraling turn back towards the runway that none of us were expecting leaving us clutching on to the seats in front us bracing ourselves as we dove towards the short mountain runway at a breakneck speed. When we finally came to a stop on the runway everyone on board sighed a deep breath of relief and applauded the pilot including us. We were quickly ushered off the plane, as flight staff turned around our plane with new passengers as soon as possible to squeeze in as many flights as possible back and forth to and from Pokhara before weather conditions soured.

Towering Mountains of Annapurna Range Over Jomsom

After landing in Jomsom, we had breakfast at a local cafe and met our 2 porters, who would be carrying 70-pound duffel bags each secured by rope tied around their foreheads. Despite the small size of our porters, they would prove to be strong.

From Jomsom we walked mostly along a gravel road to Kagbeni for an easy 4 hours getting our first glimpses of the beautiful and desolate valleys of Mustang. I was concerned that the recent construction of the road would ruin the trek and yes it definitely degraded it but the scenery and desolation of Mustang is still intact despite the road and the road was far from busy and we rarely encountered vehicle traffic and if we did it was usually a motorbike. Nonetheless I wished I could have done the same trek prior to the construction of the road, and I wondered how different the region must have been in those days.

Mustang is located in a high desert arid steppe, where rain and snow are relatively rare. This was evident by the parched dry landscape. So, when we arrived at the Tibetan village of Kagbeni, the view of the fertile irrigated fields in contrast to the dry and desolate mountain ridges and snow-clad peaks was beautiful. We checked into our local guesthouse and had a large lunch in a porch overlooking the village and the majestic Annapurna mountains, which were so tall that they would almost always be visible to us everywhere we went during our trek in Mustang. Mount Annapurna, is the 10th highest mountain in the world at 26, 545.’ Despite not being the highest mountain, it is the most dangerous in the world to climb and competes with K2 Mountain for the highest climbing fatality rate.

Kagbeni village with its ancient mud brick buildings and stone alleyways overlooked the Kaligandaki river valley from a lofty ridge irrigated with green Frields of barley and apple trees was exciting to explore. We started at the 1000-year-old monastery bustling with young student monks playing hacky sack in the courtyard while some of the older monk practiced playing the deep eerie sounding Tibetan longhorn for an upcoming festival.

Our teahouse in Kagbeni would be the most comfortable one we would stay in during our time in Mustang and it would be the last time we would have a hot shower on the trip. Most of the showers for the rest of the trip would be icy cold or via a bucket.

Green fields of Kagbeni

Domestic goats prized for their thick wool

Hike to Chele

The next morning after breakfast we set off on our trek of 6-7 hours along mostly flat terrain again mostly on the gravel road but sometimes via foot paths more direct than the road. The river canyon became deeper and more majestic and after Kagbeni we entered the Mustang restricted area where entry is only allowed with permit. Again, we encountered the occasional bus or vehicle, but they were too few to be much of a hinderance.

The typical elevation was 11,000-12,000′ and the sun was intense. Additionally, the dry conditions, and strong winds kicked up dust into our faces and we had to cover our faces with a bandana for both sun and dust protection. It was on this hike that we first started to see sky caves, manmade caves made during ancient times, dotting the cliffsides in the hundreds. The highlight of day’s hike was sleepy Thange Village, sitting on top of a cliff overlooking the Kaligandaki river valley. We loved this village because it may have been the most traditional village we encountered on our trip. Most houses were traditional mud brick, the walk into the village was through covered tunnels adorned with prayer wheels, along ancient monastery walls. Farmers tended to goats and a few village men practiced their archery skills. Life went on here as it always has. The village we discovered was one of the main villages where trekkers stayed before the construction of the road but now days it is rarely visited by tourists, and it has a raw National Geographic feel to it. The people were friendly and one man as we were exiting the village asked us if we had seen the largest stupas, large beautifully decorated conical or square shaped Buddhist structures usually containing relics or humain remains of a monk. Stupas or chortons are usually located on the outskirts of a village. We were very thankful that the man helped us find them because the ancient stupas and crumbling old fortifications of the village overlooking the majestic canyon were magical.

One of the ancient Buddhist stupas outside of Thange Village

One of the old fortified walls or monastery walls of Thange Village from ancient times

Sky Caves

There are only a few places in the world where I have observed man-made caves carved located in high inaccessible mountains: Bamiyan, Afghanistan and Dogon, Mali. But the sky caves of Mustang are the most impressive. Throughout Mustang, there are thousands of these manmade sky caves, mostly inaccessible and found hundreds of feet above the ground in sheer cliffs thousands of feet tall. The oldest ones date back to 1000 B.C. and were used for human burials. Tibetan people have long practiced the custom of sky burials where a corpse is left in the open or in this case an open cave to allow animals such as vultures to consume the flesh, which Tibetans believe recycles the life cycle. In later years, during war and periods of instability, people of the area lived in the caves for protection. Buddhist monks would also later use them as meditation chambers.

Few caves have been thoroughly explored. In some caves archeologists have discovered human remains, and treasures such as golden face shrouds, jewelry and pottery. Many caves are also decorated with Buddhist murals and relics, skeletons of animal sacrifices and evidence of smoke charred ceilings from cooking fires.

Little is known about the caves since they are so difficult to explore. The crumbling sandstone where they are located was described by one rock climber in a National Geographic expedition to explore the caves as scary and dangerous. Falling rocks and anchors coming loose from the unstable sandstone plagued the expedition and almost resulted in death.

Then there is the mystery of how the caves where built. No one knows for sure, but one theory is that vertical shafts were carved out from the top of the mountains and rope ladders were used to descent down into the caves and over time with erosion and earthquakes, the face of the cliffs have fallen revealing many of the caves, which would have otherwise remained concealed underground.

Today the caves are considered sacred by the Tibetan people of Mustang and even though most are not accessible and even if they were they are considered dangerous to climb even from professional rock climbers and danger aside, permission must be first obtained by the local people, who are weary of looters.

Hike to Ghiling Village

Chele village was at an elevation above 11,000′ foot. The nights in Mustang were always cold dipping down to around freezing but the intensity of the sun during the day was strong even so that the temperature would reach 70 degrees. The ultraviolet rays of the sun were always at maximum strength and any skin exposure to the sun of more than 10 minutes would cause a sun burn.

After waking up in the cold morning to a village full of woodsmoke used in all of the village houses for warmth during the cold nights, we set off on the longest and most grueling hike of the trip to Drakmar Village. The hike was likely hardest because we were still acclimatizing to the high elevation and a significant portion of our trekking now was uphill on steep footpaths that would take us above 13,000′. We began the hike by climbing 1000′ and then we climbed another 1000′ over a mountain pass before having to descend into a steep canyon that rivaled the Grand Canyon in size and beauty. Giant 10′-winged griffin vultures were commonplace soaring above us keeping a close eye out for carrion. We hiked to Chungso Cave Monastery at the bottom of the canyon and then one last grueling ascent out of the canyon to the village of Ghiling village arriving late in the afternoon.

View from my room in the tea house of Chele Village

Suspension bridges are commonly found in Nepal connecting villages that would otherwise be hours apart from each other. All are feats of engineering genius, and some are suspended hundreds of feet over the canyons below.

Me resting on top of the mountain pass

Jimmie, Jesse and I on top of the pass

A highlight of the long hike to Drakmar Village was visiting the remote Chungsi cave monastery believed to have been the meditation retreat of the famous Tibetan saint, Guru Rinpoche, who is credited with bringing Buddhism to Tibet. When we arrived at the cave, we walked in and were greeted by a group of friendly monks, and a few local village pilgrims, an elderly lady and her young granddaughter. Her granddaughter, cast us repeated bashful smiles and giggled. She snuck a few photos of us with her phone and when I took a photo of her, she blushed and was immediately scolded by her grandma in their Tibetan language probably for being too friendly with us. The language of an elder women’s scorn of a young girl is universal and does not require translation no matter the language. The grandma cooked us ramen noodles and tea in the gas stove located inside the cave, which we were happy to receive since we were starving. After we ate, we walked around the cave and saw the monk’s sleeping quarters made of wood and mud brick built into the inside of the cave and behind the room in the natural part of the cave was a giant bronze statue of Buddha and small stalactite shaped Buddhas. When our guide mentioned to the monks that it was Jimmie’s birthday, the monks offered to perform a ritual of blessing for Jimmie. We all sat before the giant Buddha while the monks performed a 10-minute-long ritual of a Buddhist blessing for Jimmie, which concluded with them laying a white cloth like ribbon of honor around his neck, which he wore for the remainder of the hike.

Ghiling was a serene, remote and traditional village with a beautiful cliffside monastery that we wish we had an extra day to explore but we were too exhausted at the end of the long trek and all we could do was reserve our strength for the next day’s hike. We enjoyed our teahouse stay. Teahouses were all the same. The mother of the family that owned it was always slaving away in the kitchen, sometimes with the help of her daughters. We discovered that some of the women in our teahouses had multiple husbands, the Tibetan custom of polyandry, where a woman will be married to two brothers in order to keep family inheritances from leaving the family after death.

All the families we stayed with were friendly, and we usually stayed in rooms located on the second floor sometimes only accessible via a small rickety wooden ladder. Jesse and I shared a dusty room with blankets on our beds that have likely rarely been cleaned in between guests. There was a squat toilet and no shower and a comfortable shared room, where we ate our meals, usually vegetable momos or dumplings, dalbat or fried rice with tea and sometimes warm beer.

The village monastery which we could see out our room’s window

We woke up as always to eggs, tea and for me oatmeal and peanut butter, which I brought from home to boost my hiking energy in mornings. Then we purified some water and set off on what was always an immediate steep uphill hike. We followed the shepherd trails above the village to a high pass overlooking the village and the surrounding mountains. We hiked through the village of Ghami, across a river and up and over another huge pass. My map indicated we were in an area of blue sheep sightings and sure enough like clockwork we came across a wild blue sheep crossing the trail being pursued by two Tibetan mastiff dogs. The village of Dakmar off the main road was very quaint and traditional. The bridge in town had severed goat skulls hanging from it- a tradition in Mustang- and we encountered friendly smiling locals including one elderly woman in traditional robes who was meandering through town aimlessly while chanting Buddhist meditations out loud. I was surprised when I asked her for a photo when she responded by asking for money. It wasn’t much and I doubt there is a social security system in place for the elderly, so I was happy to pay it. I also learned that most people in Mustang were opposed to foreigners photographing them because in the past a tourist took some photos and published them making thousands of dollars and gaining publicity for his photos. Word of this reached the villagers, who received nothing for the photos, and they became resentful and because of this usually decline to have their photos taken or ask for a small amount of money. Monasteries are the same and photos inside of them are forbidden unless a 100USD fee is paid.

Our teahouse accommodation was even more basic than the previous night, but we were happy because this was the kind cultural experience we came seeking. Once in Drakmar village, my brother and I climbed some of the scree slopes to try and enter one of the many sky caves scattered along the radiant red sandstone cliffs bordering the village, but the entrances were just too high from the ground, and we couldn’t justify the risk of falling and breaking a limb or worse to try and free climb up into a cave passage. Just climbing and descending the scree was risky enough for us.

Wild Himalya blue sheep we encountered on the trail

A Buddhist Chorton at the beginning of Drakmar village

Elderly ladt in Drakmar Village chanting Buddhist hymns

Sky caves in Drakmar Village

Sky caves in Drakmar Village

Sky caves in Drakmar Village we tried to climb into

Sky caves in Drakmar Village

Teahouse we stayed in at Drakmar Village

Games at our tea house

Hike to Lo Manthang Village

Our last day of trekking promised to be a long and arduous one with lots of climbing across two 14000′ passes and would also be the only day of the trek when we thought we would get rained on. We started the morning climbing a 1000′ ridge up and over sky caves to a windswept plateau. A village dog-Tibetan mastiff -started following us from Drakmar Village and would hike beside Jesse for the entire 14-mile hike to Lo Manthang Village before disappearing only to reappear and say goodbye to Jesse a few days later as we were leaving Lo Manthang.

We stopped at the remote 700-year-old Ghar monastery that is considered the most powerful one in Mustang. It was damaged by the 2015 earthquake and a sigh outside of it stated millions of dollars were donated by the US government for renovation, which was ongoing during our visit. Like all monasteries we entered, we were greeted by the sweet smell of incense smoke and the shadowy, dusty interior was lit from yak butter lamps casting a pale light on the Tibetan Buddha statues that typically have scary demon like faces meant to scare evil spirits away from the monastery. The monastery was mystical and beautiful, and it was a shame no photos were allowed.

After the monastery we started our highest climb and passed flocks of goats and high alpine meadows with marmot burrows, but sadly Jesse’s new mastiff friend chased all the marmots so we couldn’t get a good look at them. We arrived in Lo Manthang in the afternoon and even though the hike was long today, we were more acclimatized and able to recover quickly, and Jesse and I were quickly on foot to explore Lo Manthang after dropping our equipment off at our tea house.

Hiking up the plateu from Drakmar Village

Stopping for tea at Ghar monstery

Ancient ruined building along the hike

Buddhist Chorton

Lo Manthang Village

We finally arrived in the capitol village; the ancient walled medieval village of Lo Manthang located only 10 miles from the Chinese Tibet border. We were in Lo Manthang just days after the Tiji festival, the most popular event of Mustang that draws hundreds of foreigners into Mustang and now that the event was over and everyone gone, we were among only a few foreigners in the village. Lo Manthang impressed us with its high stone walls and meandering narrow alleyways, some covered, leading in between mud brick houses and 1000-year-old monasteries. Cows and horses wandered the streets. Locals gathered socializing in the streets, playing local games, spinning handheld prayer wheels, and others walked the streets spinning the human sized prayer wheels. The spinning of Buddhist prayer wheels is meant to spin the prayers that are inscribed in rolled up papers inside of the wheels up to the heavens. A common sight on the streets were women in brightly colored Tibetan dresses and head scarves carrying children and baskets of barley on their backs and monks in red robes traveling in between monasteries. Yea there are tourist shops selling souvenirs and the venders approached us, but they were not too pushy and were polite. Lo Manthang had a magic about it and the magic was most powerful early in the cool morning or late in the evening. This was the time when my brother and I loved to wander the streets the most. Early one morning, we saw the giant wooden doors of a 1000-year-old mosque open and we knew it was closed so our curiosity drew us closer. Inside dozens of elder monks and even some children were conducting some kind of ritual inside and were seated beneath the giant 60′ Buddha chanting a mantra. Jesse and I sat outside the door listening in awe too encaptivated to leave but also trying hard to avoid disrupting the ritual and being disrespectful.

We stopped by the King’s Palace, but it is no longer inhabited. The elderly king recently died and the queen also elderly lives in Katmandu. The prince owns the palace and pays to maintain it but the palace appeared run down and abandoned. Its only occupant a single giant beast of a Tibetan mastiff guard dog chained to a post of the 2nd floor facing the street below and viciously barking at anyone passing by. The huge dog was given to the king as a present when he was a puppy and sadly has never left the 2nd floor or is removed from its chain.

Local man spinning the prayer wheels.

Locals in town that sit, and watch life idly go by while spinning their prayer wheels. One of the old men was wearing an old-fashioned pair pf mountaineering goggles I was told was gifted to him by an old mountaineer when he was young. The goggles are so rare and valuable now that he was offered 20,000USD for them by a wealthy collector but he refused because he likes them.

Lo Manthang streets

Buddhist monastery students

Kings Palace

Tibeten mastiff guarding kings palace

Unique bird sitting in the firewood commonly stored on the rooftops of most homes along with drying cow dung for fuel

View of Lo Manthang Rooftops with firewood and cow dung used as fuel for heat and cooking lying on the roof tops

In the distance over the walls of Lomanthang we could see a Chinese watch tower on the China Tibet border. One of the locals discussed China and its persecution of Tibetan people and how the people are grateful for Chinese investment into the area but not trusting of them and pleased with their treatment of Tibetans and their culture. He said that there is a large telescope in the watch tower that is capable of seeing every person that visits Lomanthang and is especially used when high level monks visit town such as the Dala Lama and beyond that he knows that Chinese spies would also be present. People of Lo Manthang are allowed to cross the border into China occasionally during market days but any photos or references to the Dalai lama or anything else deemed conspiratorial by China is confiscated and the perpetrator could face imprisonment. When I asked the same villager if there were any wars in modern times that impacted Mustang, his response was only with China when It invaded Tibet it also tried to take Mustang too.

Day of Visiting Sky Caves and Horseback Riding on My Birthday

On the day after finishing our trek, my 46th birthday, we hired horses and for a 3 hour round trip journey to the Jhong sky caves with 40 rooms that were accessible via ladders to tourists and a few cave monasteries. It was a good relaxing way to reach the sky caves and some of the outer villages without having to hike and the horses mostly behaved themselves, something I am weary of ever since I had a horse run off uncontrollably though the Colombian jungle over a decade ago leaving me with chronic horseback riding PTSD.

Jesse on horseback

Tibeten women collecting drinking water from a stream

Village Lady

Cave Monastery

Jesse in cave monastery lloking at the ancient Buddhist life cycle paintings on its wall. The monk in charge of this monastery only allowed me to take photos when I slipped him 10USD in equaivalent rupees.

Crawling around inside sky caves

Us inside sky caves

The most exciting part of the day happened when Jesse and I mentioned to the young son of the family who owned our tea house that were going to hike to the hot springs and sky caves located near them. I asked him if he would join us and he was quick to say that he would love to but his mother, being very superstitious, would not allow him to walk that way near dark since there was a sky burial site nearby and she believed the area is haunted by spirits When he mentioned sky burial my interest was piqued and I convinced him to join if we went via jeep, which would get us back before dark avoiding his mother’s ire. We planned to visit the sky burial grounds and also some of the wilder sky caves located outside of Lo Manthang, which were rarely visited by tourists because the infrastructure to climb them was not there and conditions were more dangerous. Our new guide was familiar with the caves and according to him he and his friends as young teenagers would climb and explore them often pushing the safety envelope. After the caves, we planned to stop by the small hot springs in the river close to the sky caves where one of the ancient monks claimed dark energy was being released, which was later discovered to be because of the massive uranium reserved located underground.

Sky Burial Site

We pulled over to an overlook a few miles outside of Lo Manthang in a remote canyon with a small creek running through it. Below s a few hundred feet away near the stream was a small stone enclosure and an open field where the sky burials are performed. Corpses of the deceased in Mustang meet one of two fates-cremation usually reserved for monks or other princely people of title or via sky burial, where a body is cut into small pieces and left out in the open for the vultures to consume. This is believed to re-set the lifecycle that all Buddhists believe in. A designated man in Lo Manthang carves up the bodies in the small stone structure and I was told is paid well for this and if for any reason he is not available, a family member is responsible for performing this grizzly duty. Once a body is cut into small pieces it is strewn out in the open and a prayer is given for the soul of the deceased asking for the arrival of the vultures, which almost always come. If the vultures do not come, I was told it is because the soul of the dead person was bad, and they did bad things in life.

We peered down below looking for skeletons or any body parts but there were no sky burials currently in progress and any evidence of old skeletons would have been placed into the stream to be washed away so between that and the vultures nothing remained in the fields below and won’t until the next person in the region dies.

Sky burial site

We reached the sky caves after an hour drive on a rough 4WD road and then crossed a river via a suspension bridge. There were multiple levels of caves and to reach each level, some rock climbing was required. The caves lacked infrastructure for tourism and visiting them involved climbing up scree slope, scaling vertical shafts with loose rock and hugging the scrambling across ledges on top of drop offs. There were small offerings of shells left inside the caves and some Buddhist murals and painting remnants on the walls.

Sky caves located at the bottom portion of the huge mountain

Exploring the caves was a lot of fun especially since there was no one else within miles in any direction but climbing the loose scree and using foot and hand holds while ascending vertical shafts of crumbling sandstone was too risky to do for long. After exploring the caves, we returned to our tea house and had dinner with a cake for my birthday that was baked in the only bakery in Lo Manthang.

Sky caves

Buddhist murals on wall

Jesse in one of the caves

Me carefully sliding down from an entrance of a cave

Our guide climbing one of the vertical shafts leading to more layers of sky caves above us.

Long Treacherous Drive to Pokhara

On our last morning, I purchased what is probably what is he most unique souvenir; a Tibetan flute or kangling, which is made out of the femur of a deceased monk. The kangling is played by Tibetan monks in Buddhist rituals to subjugate demons. My concern was immigration, both Nepalese and United States would seize it but, in the end, I was able to bring my new kangling home with no issues.

From Lo Manthang we drove 6 hours via a jeep to Jomsom, where we spent the night in a tea house. The next morning the conditions were stormy and all flights out of Jomsom were cancelled and likely to be cancelled for days so we hired a jeep to take us to Pokhara via a long grueling 8 hour drive in muddy 4WD conditions.

4WD Road to Pokhura

Pokhura

We loved the relaxing vibes of Pokhara and its jungle clad lakes, tourist friendly environment with great local eateries and bars so much that we spent two nights relaxing there, getting a massage, eating at nice restaurants and exploring. One of the highlights was visiting the Pokhara Disneyland with its creepy Micky Mouse Statues and bumper cars.

Pokhura Lake

Disneyland

Joining a street dance with Hara Krishnas

Katmandu & the Living Child Goddess

From Katmandu, Jimmie and I flew via a 20-minute Buddha Air flight to Kathmandu via the newly Chinese built Pokhara airport and I spent my last night exploring Durbar Square before flying home via Qatar Air in the evening. From our hotel, Jimmie and I walked to Durbar Square braving the lack of shoulders on the roads and the crushing pedestrian, vehicle and motorbike traffic in the pollution choked streets of Katmandu. I wanted to see the effects of the earthquake of 2015 that killed 9000 people, mostly in Katmandu, and I also wanted to see the cultural and historical center of the city-Durbar Square. Durbar although exhausting to visit, was far from boring and was a constant assault on the senses. We were constantly accosted by touts, wannabe guides, beggars, and stepping over dead animals in the streets but the old wooden architecture mixed with Chinese and Indian styles was breathtaking. There were Hindu temples, Buddhist stupas, and wandering Hindy Saddhu holy men with painted faces. There were still some damaged buildings from the earthquake, but most appeared to have been repaired. It was a fascinating but challenging place to visit.

The weirdest place we stumbled upon was the palace of the living Hindy child Goddess or Kumari. The child Goddess is selected at birth from a group of babies from a Buddhist village in the Katmandu Valley by a group of Hindu priests with scary masks and severed goat heads. The baby that doesn’t cry or cries the least from this heinous spectacle is crowned the Hindu Goddess or Kumari. The Kumari is separated from her parents and placed in this palace in Durbar square where she will live until puberty. There are other Kumari’s throughout the Katmandu Valey in addition to her, but she is the most prominent one. The Kumari is not allowed to socialize and have a normal childhood. She is not allowed to touch the ground and it is believed that any man who marries her will die within 6 months. For a few moments twice a day, she is allowed to stand in her porch dressed in full makeup and her customary head dress while dozens of paying curious tourists gawk at her from below. When I stood at the entrance gate before her palace, an Indian man and his small child next to me were hoping to catch a glimpse. The Indian man whispered to his child, ” look this is where we will see the living, Goddess”.