Journey to the West Bank and Israel

November 2025: A Five-Day Expedition to the Biblical Lands

For a brief five-day adventure, I traveled through the Palestinian Territory of the West Bank and Israel, dedicating three days to the West Bank and two days to Israel. My main goal was to explore the world’s largest salt cave, a natural wonder that some believe marks the location of the biblical city of Sodom, said to have been destroyed by God for its wickedness.

A Region in the Headlines

The Palestinian territories had been in the news a lot lately—and not for good reasons. Hamas militants, which ruled Gaza, launched a devastating attack on Israel on October 7,2023. In retaliation, Israel decimated Gaza, leaving around 60,000 people dead. I had long wanted to visit Gaza, but that is no longer possible or even realistic. Instead, I focused my journey on the other Palestinian territory, the West Bank.

Unlike Gaza, the West Bank sits on the opposite side of Israel and remains far more peaceful, though it still experiences occasional skirmishes between Israeli settlers and Palestinians, as well as Israeli Defense Force raids.

Returning After Two Decades

My desire to visit the West Bank went beyond curiosity. I wanted to hear directly from the Palestinian people and see with my own eyes what life there was really like. More than twenty years earlier, I had passed briefly through the West Bank while traveling from Jordan to Jerusalem and back. This time, I wanted to give the region a proper visit—to explore its deep biblical history and understand, through firsthand conversations, what it means to live as a Palestinian under Israeli control.

Arrival and Exploration

Together with a few friends, I flew into Tel Aviv, then journeyed across the desert landscape to spend two nights in Jericho and Bethlehem—two of the most historically and spiritually significant cities in the West Bank.

Palestinian Territory of the West Bank

Me seated in United Polaris Business Class

Business Class Lie Down Seat

Life in the West Bank

A Divided Land

The Palestinians have lived under Israeli control for decades, often as second-class citizens in their own homeland. During my first brief crossing of the West Bank more than twenty years ago, I witnessed glimpses of this reality. Over the years, I’ve also heard countless stories from Palestinian friends about the daily struggles faced by families in both the West Bank and Gaza.

Generations of Palestinians were displaced from their ancestral lands following Israel’s founding, with many ending up in refugee camps—some abroad, others within the West Bank—where life remains difficult and opportunities limited.

The Separation Wall and Control

Israel controls the borders of the Palestinian territories and decides what moves in or out. A twenty-foot-tall concrete barrier—called the security wall by Israel and the separation wall by Palestinians—divides much of the West Bank from Israel. Driving along it, the contrast between the two sides is striking. The economic gap is staggering, with Israeli towns prosperous and well-developed, while many Palestinian communities struggle with poverty and restricted mobility.

The Ongoing Struggle

Palestinians have long sought their own state, a goal championed by the Palestine Liberation Organization since 1964. Israel, citing both security concerns and biblical claims to the land, has opposed or limited these efforts. Backed by strong U.S. support and one of the most powerful militaries in the world, Israel continues to expand settlements across the West Bank—today numbering around 300,000 residents—many of which are guarded by the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF). These settlements are a constant source of friction and, at times, deadly clashes between settlers and Palestinians.

Gaza and Its Consequences

While the West Bank is governed by the more moderate Palestinian Authority, the Gaza Strip is ruled by Hamas, a militant faction long in conflict with Israel. In October 2023, Hamas launched a brutal attack on Israel, crossing the border using hang gliders, kidnapping dozens of Israelis, and killing more than a thousand civilians. Israel’s massive military response devastated Gaza’s infrastructure in an attempt to eliminate Hamas and rescue hostages. Over 60,000 Palestinians—many of them civilians—were reported killed. Images of wounded and dead children filled the news, though perspectives varied widely depending on media sources and political bias.

In the West Bank, people told me they felt collectively punished for Gaza’s actions. Jobs in Israel vanished, tourism collapsed, and travel restrictions tightened. Daily life became even more difficult.

Symbols of Resistance

Everywhere I went, I saw symbols of Palestinian resistance and loss. In one small convenience store, a poster of Saddam Hussein holding an AK-47 hung beside photographs of young Palestinian men—martyrs, as locals called them—who had been killed by the IDF. Saddam, though a dictator elsewhere, is remembered here by some for his vocal support of the Palestinian cause. These martyr posters were displayed openly across towns and villages, serving as a somber reminder of the human cost of the conflict.

In Jericho at my hotel, I came across a large mural of Yassir Arafat, one of the founding members of the Palestinian Liberation Organization

A poster of Saddam Hussein, the late Iraqi leader, holding an assault rifle displayed proudly beside several photographs of young Palestinian men who, I was told, had been killed by the Israeli military.

Image ofa Palestinian martyr on a post lining the street that I was told was killed by IDF

Arrival in Israel

Day 1-Navigating the World’s Strictest Border

I traveled to the West Bank with my friends Dan, Jimmie, Richard, and Richard’s son, Wes. Our first night was planned in the ancient desert city of Jericho—but first, we had to get there. That meant flying into Tel Aviv’s Ben Gurion Airport, long known among travelers for having some of the strictest entry procedures in the world.

I was a little anxious. My passport still carried an Afghan stamp, which I worried might raise red flags and lead to extra questioning. I also had friends who are outspoken critics of Israeli foreign policy, so before the trip, I deleted old messages just to avoid unnecessary complications. Israel is famously sensitive about foreign visitors—especially journalists or activists who might be seen as politically involved in the West Bank.

Through Border Control

Surprisingly, we had no issues. The border guard asked about our travel plans, wanting to know where we would be each day. I didn’t hide anything. When asked why we wanted to visit the West Bank, I gave a simple, truthful answer: we planned to visit Christian historical sites. That seemed satisfactory, and we were admitted without further delay.

Meeting Our Driver

Outside the airport, we met our Palestinian driver—a Catholic Christian born in East Jerusalem. Because of long-standing political agreements dating back to the Jordanian era, he has special identification that allows him to travel freely between Israel and the West Bank, a privilege most Palestinians do not have.

Even with these permissions, he wasn’t immune to scrutiny. When he entered the airport’s security perimeter to pick us up, he was pulled aside, questioned, and his vehicle searched. My friend Dan, who had arrived a day earlier and was riding with him, said the inspection went smoothly only because he was present as a foreigner.

The driver came highly recommended by my friend Bryce, who has visited the West Bank many times, and it didn’t take long for us to see why. He was not only fun and full of energy but also incredibly knowledgeable about the region’s history, religion, and politics.

Into the Desert Night

By the time we left Tel Aviv, night had fallen. The drive to Jericho took about an hour and a half. We passed Jerusalem, climbed over the highlands, and then began a long descent through the desert toward the Jordan Valley. Jericho lies nearly 1,000 feet below sea level, making it one of the lowest and oldest continuously inhabited cities on earth.

Set between the mountains of Judea and the Jordan River, Jericho is a true desert oasis—a patchwork of palm trees and farmland surrounded by the harsh, barren landscapes of the Judean Desert. Its fertile springs have drawn settlers for over 10,000 years, earning it the title “City of Palms.”

Ancient Biblical City of Jericho

Few places in the world carry as much layered history as Jericho. In biblical times, its ancient brick walls were said to have been brought down by the divine power of God working through the Ark of the Covenant, carried by the Israelites into battle. Centuries later, King Herod built a grand winter palace here and is believed to have died in the city.

Jericho also holds deep significance in the life of Jesus. According to the Gospels, he passed through the city on his way to Jerusalem and later retreated into the desert mountains above it to fast for forty days and nights, where he was tempted by the devil. Standing in Jericho today, surrounded by desert and ancient ruins, it’s impossible not to feel the weight of history pressing in from every direction.

Crossing into the West Bank

Along the way, we crossed through the West Bank’s Zones A, B, and C—administrative divisions created under the Oslo Accords that make the region’s governance even more complex. Our driver explained that Israelis are allowed to enter and even live in some zones, but not in others. When we approached Jericho, a large red sign warned that it was illegal and unsafe for Israeli citizens to enter. The gate was guarded by IDF soldiers, but they waved us through without issue.

First Impressions of Jericho

Inside Jericho, the streets were lively. Arab men chatted outside cafés, and concrete buildings stood half-finished under the warm desert air. The call to prayer echoed from mosque loudspeakers as we said goodnight to our driver, checked into our hotel, and set off to find dinner.

We ended up at a small restaurant serving fish, accompanied—without warning—by at least twenty small side dishes. Plates of hummus, warm bread, pickled vegetables, and roasted eggplant filled the table. It was a feast, and we quickly learned that in the West Bank, even the simplest meal often comes with overwhelming generosity.

Day 2 – Exploring Ancient Jericho

The Mount of Temptation

In the morning, we enjoyed a generous, multi-course breakfast provided by the hotel. The sun was already warm and bright, and we were eager to begin exploring Jericho. Our driver arrived and took us to our first stop of the day, the cable car that leads up to the Mount of Temptation, the site where, according to Christian tradition, Jesus fasted for forty days and was tempted by the devil.

The Ascent

The mount rises dramatically from the desert floor, its sheer cliffs glowing gold under the sun. Built into the rock face is a small Greek Orthodox monastery said to mark the cave where Jesus meditated. The structure was built about a thousand years ago, and nearby, dozens of other cave monasteries dating back to medieval times dot the mountainside, once home to monks who lived in complete isolation and prayer.

To reach the site, visitors can either hike a steep, dusty trail or take the rickety old cable car that sways across the valley. We chose the cable car, though it looked as if it hadn’t been used much in recent years. Before we boarded, our driver casually mentioned that not long ago, the cable car had shut down mid-ride, trapping passengers for several hours in the heat. We laughed nervously at the story but didn’t think much of it—until we were high above the valley and our car suddenly stopped.

For several long minutes, we hung suspended a hundred feet above the desert floor, baking in the sun and wondering if we were about to repeat that story ourselves. Eventually, the car jolted back to life and resumed its slow climb toward the monastery station.

The Cave Monasteries

At the top, we visited the main monastery carved into the cliff. Its caretaker, an elderly Greek Orthodox priest, seemed unimpressed by visitors, and photos were strictly forbidden. The place felt solemn but somewhat unwelcoming. What drew us most were the unmaintained cave monasteries along a narrow side path further up the mountain.

The access gate appeared to have been left open, so we wandered inside carefully. These hidden caves were hauntingly beautiful—ancient chapels hollowed into the rock, decorated with faded frescoes of saints, some with their faces scratched out, likely during Muslim conquests centuries ago. Layers of history clung to the walls; every mark told a story of faith and conflict.

Wildlife Among the Ruins

As we explored, rock hyraxes—small, furry animals that resemble oversized guinea pigs—darted among the stones, perching on ledges to watch us curiously. Their presence, along with the silence of the desert and the wind sweeping through the cliffs, gave the mountain an ageless, almost mystical atmosphere.

Dan and Richard in the rickety cable car to the Mount of Temptation, the site where, according to Christian tradition, Jesus fasted for forty days and was tempted by the devil.

Mount of Temptation, home to a Greek Orthodox church marking the location where, according to Christian tradition, Jesus fasted for forty days and was tempted by the devil.

Numerous Cave Monasteries with more impressive findings scattered about the Mountain

Rock Hyrax

Exploring Abandoned Monastery Caves

Old Crumbling Wooden Altar in One Abandoned Monastery Cave

Wall mural with faces scratched off likely by invading Muslim Armies Over the Last few Centuries

Ancient City of Jericho

Descending into a Pit, probably off limits, in the ancient city of Jericho

Road to Kypros castle through the Judean Desert

King Herod’s Kypros castle

Israeli War Bunker on Kypros castle

Exploring King Herod’s Kypros Castle

View of Jericho from the Top of King Herod’s Kypros Castle

Herodium View

Herodium Tunnels

Herodium Tunnels

The church’s famously low doorway, known as the Door of Humility, which requires every visitor to stoop while entering—a symbolic act of reverence at the site where Christ was born.

Grotto with asbestos murals beneath the Church of the Nativity, where Jesus is believed to have been born

Greek Orthodox monks and priests paying homage at the exact spot where Jesus is traditionally believed to have been born inside the Grotto of the Nativity in Bethlehem. The dimly lit cave glows with candlelight and incense as they kneel in quiet prayer before the silver star marking the birthplace of Christ.

The silver star marking the birthplace of Christ.

Cave of monk skeletons

Separation Wall

Separation Wall-Mural of Palestinian Girl killed by IDF

A Palestinian Journalist Killed in Gaza

Depiction of IDF Soldier with KKK Hood

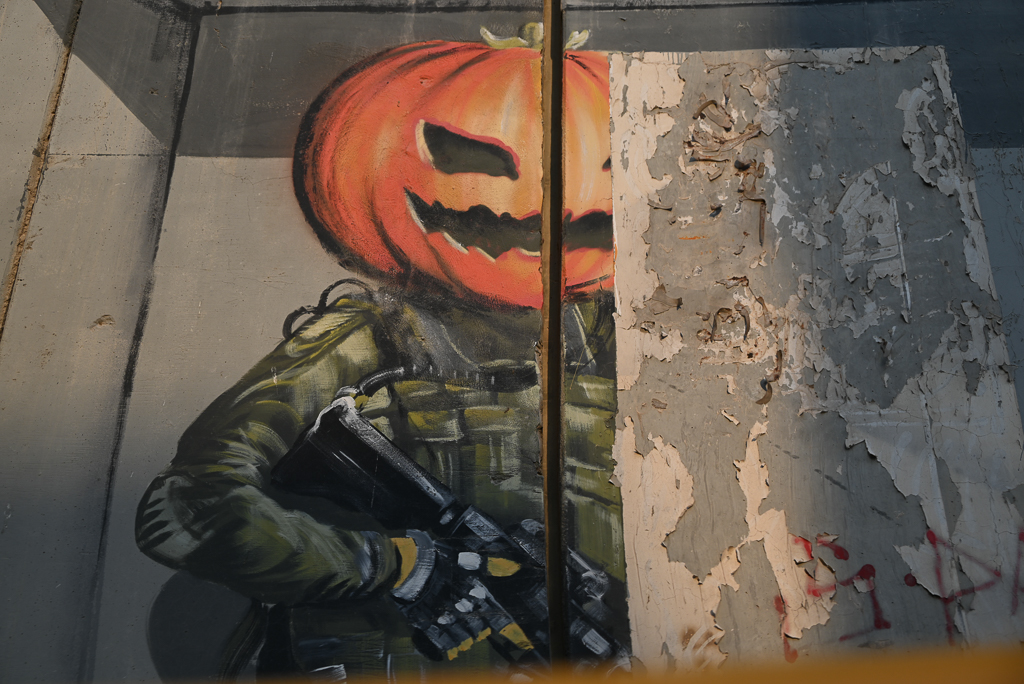

Depiction of IDF Soldier with a Pumpkin Head

Walled Off Hotel

Dans Room with Banksy Mural of IDF Soldier and Palestinian having a Pillow Fight-Walled Off Hotel

Tour of the Presidential Suite

Presidential Suite Bed

Meal of Palestinian Dish-Upside Down

All of us with a Palestinian family

Me Holding the Baby of the Family

Unfinished Apartment on Rooftop

View of Bethelehem from Rooftop

Plot of soil from the grandfather’s ancestral village in Israel